"From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and Sofia..." Winston Churchill's words, uttered in Fulton, Missouri, in March 1946, come back to me whenever I visit Szczecin. Poland's post-Yalta location, hundreds of kilometres west of its prewar borders.

Incidentally, Szczecin is not actually in the Baltic, nor on the Baltic nor even by the Baltic; it lies on the south side of the Szczecin Lagoon (zalew Szczeciński) and is 66km (41 miles) by navigable waterway from the open sea. That's further inland than the Canary Wharf is from the North Sea.

The architects of the postwar order drew up Poland's western borders along the Oder (Odra) and Neisse (Nysa) rivers. Stettin, which had for centuries served as Berlin's port, found itself in postwar communist Poland. Yet the city stands on the other side of the Oder. Any residual German irredentism is now history; the 1990 Final Settlement with Germany made that clear. Stalin had gifted Stettin for Poland in exchange for keeping Königsberg (now Kaliningrad) as an ice-free port for the Soviet navy.

Today's Szczecin has many reminders of its history. The building below, now an educational facility, had served as a reception point of the state repatriation office (Państwowy Urząd Repatriacyjny). Poles from the east of prewar Poland, having been forcibly resettled in an act of ethnic cleansing, were moved west to replace the German population that had itself been ethnically cleansed. However, this building served less typical cases... (Click to enlarge to see the ghost sign)

Below: zooming into the ghost sign above the side gate: "Reception point for repatriates from the West - Stage 2". "Repatriates from the West" would have been members of the Polish armed forces in the UK as well as Poles released from PoW and forced-labour camps in Germany, all of whom had lost their homes in eastern Poland.

In the immediate aftermath of war, the Germans who had not fled the advancing Red Army were forcibly ousted from lands that had been given to Poland in the Yalta and Potsdam settlements. The Polish repatriates were shipped into empty cities and given the choice of prime properties - few chose Szczecin, and those that did were initially reluctant to invest it its future, "in case the Germans ever came back." And so a city of almost 400,000 in 1939, had a population only half that number well into the 1960s. To this day, Szczecin's population density is far lower than other Polish cities - nearly three times lower than Warsaw's, for example. Yet Szczecin (now back up to its pre-war population) is more populous than Bydgoszcz, Lublin or Białystok.

Szczecin has improved massively in recent years as a result of large public- and private-sector investment. It is still under construction, with many roads in the centre closed for refurbishment. Wide avenues designed by Haussmann (he of the Paris renovation of the 1850s and '60s) give the city a prosperous air; large villas line the avenues, there are plenty of trees and lawns and parkland. Today, investors tend to be from Scandinavia or Germany, focusing on manufacturing and logistics (massively). There's little going on by way of shared services or business-process outsourcing here. And few office buildings.

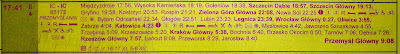

After an investment conference at the new football stadium on the edge of town, I took a train to the port of Świnoujście, just 66km away from Szczecin by river, but by train, the two are separated by journey times from 1hr 21mins (the fastest InterCity connection) to 1hr 40mins on the all-stations local service. All trains stop at Goleniów, for Szczecin's international airport, and at the seaside resort of Międzyzdroje. My local train arrived over 20 minutes late; it was held at Goleniów to let a massively delayed InterCity service through.

Świnoujście itself is another geographical oddity served up by the postwar settlement. The port town straddles the river Świna; in English, it would be called 'Swinmouth'. The two parts of Świnoujscie are connected only by pair of ferries that shuttle across the strait every 20 minutes. Car traffic is restricted to local vehicles on ZSW number plates (or with permission from the local authority) between 4am and midnight. The only alternative to this journey of 675 metres is a 235km (145 mile) international jaunt, all the way around the Szczecin lagoon, through Germany and back into Poland. Or cross at night (the ferry offers a 24-hour service).

Fearing that I might be stranded on the far shore and would miss my night train back to Warsaw, I decided not to cross into Świnoujście proper, but just to explore the port that lies on the eastern bank of the Świna strait. The ferry will be augmented by a road tunnel (to be opened next year). Sadly, it won't be for pedestrians or cyclists, who will have to take a bus or stick with the ferry.

Below: the ramp onto the Bielik ('white-tailed sea eagle') II, one of four vessels (named Bielik I to IV) serving the route. Between 04:20 and 23:40, two ferries shuttle backwards and forwards every 20 minutes, between 00:00 and 04:00 they go once every 40 minutes and will take all cars for free, wherever they're from.

I walked from Świnoujście station to Świnoujście Port, the final station along the line. Actually, the two can be considered one station, joined by a very long platform. Only local trains run into the Port station; InterCity trains terminate at the main Świnoujście station, and if you want to take a ferry to Scandinavia from the port having arrived by InterCity, you have to walk to the Port station. It's just seven minutes on foot, two minutes by local train, but there are only five pairs of trains a day serving it (really timed for the convenience of the port's employees). Below: the last train of the day sets off from Świnoujście Port back to Szczecin. Behind the station and its limited, bus-stop like facilities, stands the ferry terminal. The place reminded me of a modern version of Boulogne-Maritime and Boulogne-Ville stations back in the 1960s.

More unusual still is the station across the Świna in the main part of town - Świnoujście Centrum. The only station lying within Poland's borders that is connected to no other Polish station, and the only one to be served exclusively by a foreign rail operator - in this case, UBB. Below: image from Google Maps Street View showing the station in the tourist season. The station is located at the end of the built-up part of town, on the edge of a forest belt that stretches up to the border itself. It's 1,500m from here to the border. An hourly local service connects Świnoujście Centrum with Züssow, calling at several German seaside resorts along the way.

Back to Świnoujście's main station to catch my night train back to Warsaw. The carriages arrive with 40 minutes in hand, so good time to settle in, change into me jim-jams and be lying comfortably in bed as the train sets off. Below: the rake of coaches making up the train arrives at the platform; the electric loco that will haul it stands to the right, in retro PKP livery. Sleeper cars at the rear.

Below: the diesel shunter that has lined up the coaches departs. The rear coach, visible in this photo, has full sleeper facilities (a bed with bedding); the penultimate coach has just couchette sleeping (nothing more than a surface to lie down in your day clothes; no bedding, six berths to a compartment.). Every other coach is standard - and I can tell you that trying to sleep while seated is no fun whatsoever. I would recommend paying the extra for a two-berth compartment rather than one for three - this train was full despite it being December.

This time six years ago:

Early winter travels: Warsaw-Kraków-Poznań-Warsaw

This time seven years ago:

Patriotism and nationalism: what's the difference?

This time eight years ago:

Poland's progress in the international rankings

This time nine years ago:

The Transparency International Corruption Perception Index for 2013

Also this time ten years ago:

Poland's rapid advance up the education league table: PISA 2013

This time 11 years ago:

Life expectancy across the EU: more comparisons

No comments:

Post a Comment